Economic growth

Signs of slower growth than some had originally expected, amid supply constraints and a Covid-19 resurgence, have led to lower growth forecasts for the United States. Expectations are that the US should reach its pre-pandemic growth trend in the first quarter of 2022, rather than late 2021.

Across the euro area, hospitalisations appear to have peaked with daily new cases of Covid-19 falling in previous hot spots such as Spain and France. There is also an expectation of decent economic growth here in the UK.

Risks to economic growth remain tilted to the downside in China, though the most recent outbreak of Covid-19 appears under control. Chinese government data shows slowing growth in both industrial production and retail sales. But there is an expectation of stronger readings in September. August export data was also stronger than expected.

Covid-19 continues to tell a mixed story in emerging markets. Emerging Asia, which some had hoped at the start of the year to be the strongest emerging region for growth, has been beset by low vaccination rates and given its many zero-Covid lockdown approaches, a low rate of infection-acquired immunity as well. It has struggled with rising case counts for much of August. Latin America, meanwhile, which was hit hard by the virus around midyear, has continued to see case counts fall in recent weeks. The key will be the degree to which some of the world’s more developed emerging markets, like South Korea, might be able to use their relatively higher vaccination rates to move away from zero-Covid lockdown approaches that can weigh on growth.

Monetary policy

The Bank of England (BOE) maintained the bank rate at 0.1% at its 5 August Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) meeting but delivered a hawkish tone. Many anticipate now expect the BOE to begin to raise the bank rate earlier than before, perhaps in the second half of 2022. The bank foresees inflation peaking at 4% by year’s end. The MPC voted to leave the target for the bank’s stock of asset purchases at £895 billion which many expect to continue until around the end of the year. The bank additionally confirmed that it would raise interest rates before it begins to reduce its balance sheet. But it lowered its threshold interest rate at which the balance sheet run-off could start, from 1.5% to 0.5%.

Minutes of the US Federal Open Market Committee’s (FOMC’s) 27-28 July meeting suggest the Federal Reserve plans to start reducing the pace of its asset purchases this year.

The European Central Bank (ECB) said on 9 September that it would moderately slow the pace of asset purchases under the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP), which is scheduled to run until at least March 2022.

In emerging markets, Peru and South Korea initiated their first hikes of the post-Covid-19 cycle in August, joining Chile, Hungary, Russia, Mexico, Brazil, and Turkey. The Bank of Russia’s rate hike on 10 September, from 6.5% to 6.75%, was the fifth in a row and may not be the last.

US government funding

Many have been watching two important developments related to US government funding. The US government voted to authorise spending each fiscal year for one-third of the federal budget that is not authorised automatically until December. When it does not do so, certain government operations must be shut down. Congress additionally will soon need to raise or suspend the US debt ceiling. The administration is estimated to be able to pay the nation’s debt obligations only until an unspecified date in October in the absence of a higher or suspended debt ceiling. The likelihood of a default on US debt obligations is extremely low but given the magnitude of potential consequences of such an event, it is worth keeping an eye on.

Inflation

The inflationary environment is likely to be more volatile in the coming years than many have come to expect recently. Headline inflation reached 3.2% in August in the United Kingdom compared with a year earlier, following a 2% year-on-year rise in July. The Office for National Statistics noted that the 1.2-percentage-point one-month increase was the largest in the history of the series dating back to 1997; it also said such a rise was likely to be temporary. Underlying price pressures showed similar strength, with core inflation jumping to 3.1% compared with a year earlier, from 1.8% in July. The Eat Out to Help Out scheme, which offered restaurant discounts to support businesses emerging from Covid-19 lockdowns, helped drive the August inflation increase. With the continued run-up in global industrial prices, combined with the coming reversal of a value-added-tax cut this month and a stronger consumer demand impulse, many expect headline and core inflation to peak in the fourth quarter at around 4% and 3.5% year-on-year, respectively. Inflation should then ease over 2022 as these temporary factors unwind, with both core and headline inflation ending the year just above 2%.

Employment

The number of new jobs created in the United States fell to a seven-month low of 235,000 in July. The three-month average job growth stands at 750,000, and many anticipate average monthly job growth of around 700,000 for the rest of the year given businesses’ significant need for labour, with many potential workers facing the imminent expiration of their pandemic-related unemployment insurance benefits.

Unemployment in the euro area fell to 7.6% in July from a revised 7.8% in June on a seasonally adjusted basis and from 8.4% in July 2020. Here, meanwhile, it fell to 4.6% in the three months to July, from 4.7% in June.

The markets

In the third quarter of the year, global markets generally made minimal progress. For instance, the UK, as measured by the FTSE 100, managed to beat the US, as measured by the S&P 500, but only because the Footsie rose by 0.70% while the S&P 500 could only eke out a mere 0.23%. The S&P was dragged down by the worst September since 2011.

In Q3 the FTSE 100 was still behind the MSCI ACWI performance, but even that was below 1% in sterling terms. Japan was the strongest performer in Q3, having looked as if it would be the quarter’s laggard. Ironically the rally can be blamed on the resignation of Japan’s prime minister.

The FTSE 350 Lower Yield outperformed its Higher Yield counterpart in a continuation of the second quarter’s story, reflecting a trade favouring growth over value. The recovery trade looks to have been a Q1 phenomenon in the UK.

Inflation has prompted a rise in bond yields, although only is this obvious in the UK over the quarter. In the US and Eurozone, yields were falling until early/mid-August and then rose as inflation fears mounted.

For all the growing concerns about inflation, gold fell by 2.4% over the quarter. However, that was far from the worst performance from metals. Iron ore, often seen as a proxy for the Chinese economy, dropped in price by 46%.

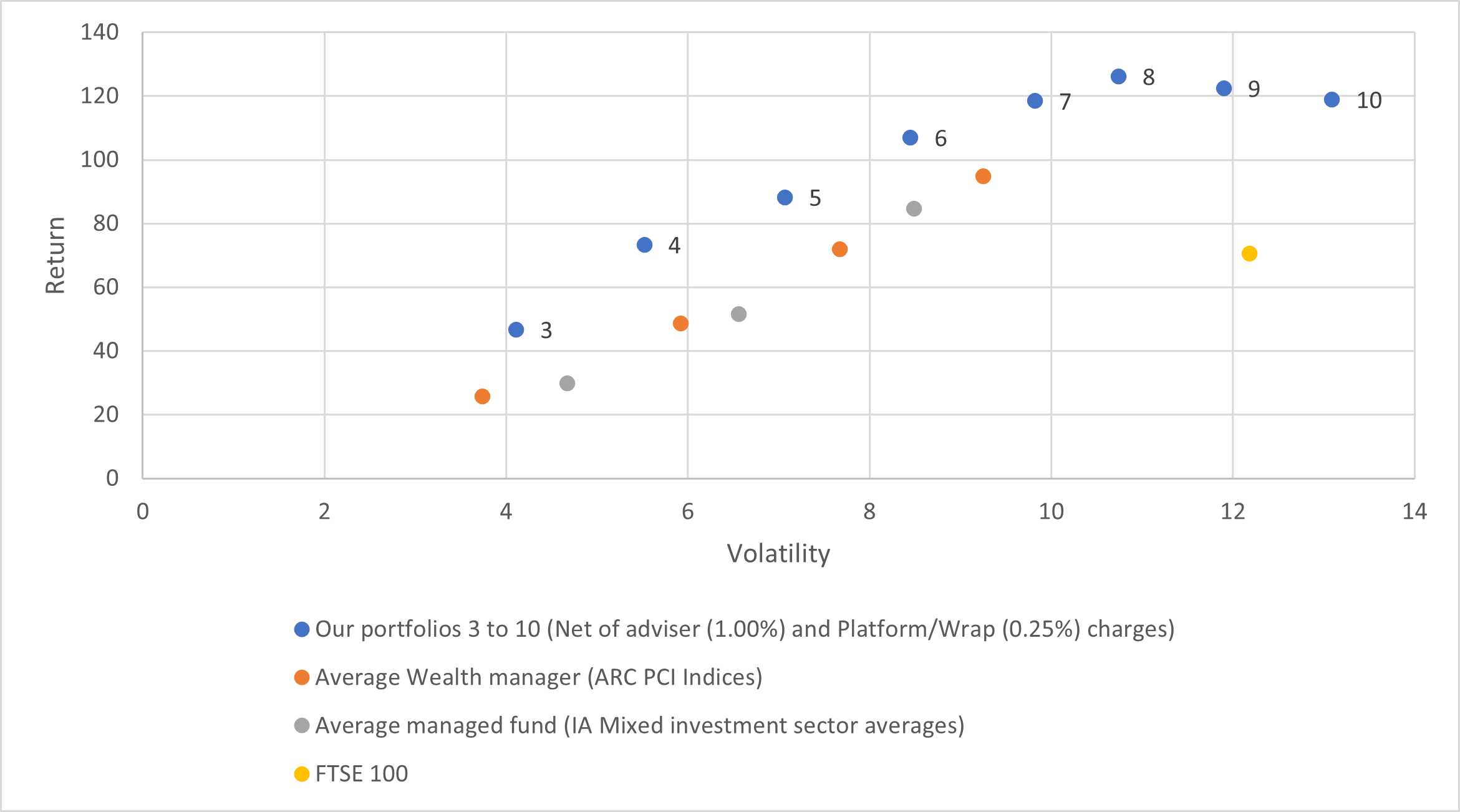

How have your portfolios done?

Our portfolios focus far more on the longer-term view than the shorter term. They do not ignore it, but we focus far more on managing risk than we do reaching for returns. Our portfolios are now more than nine years old and have gone through a full market cycle. As you can see below, they have outperformed the average wealth manager and managed fund since they started:

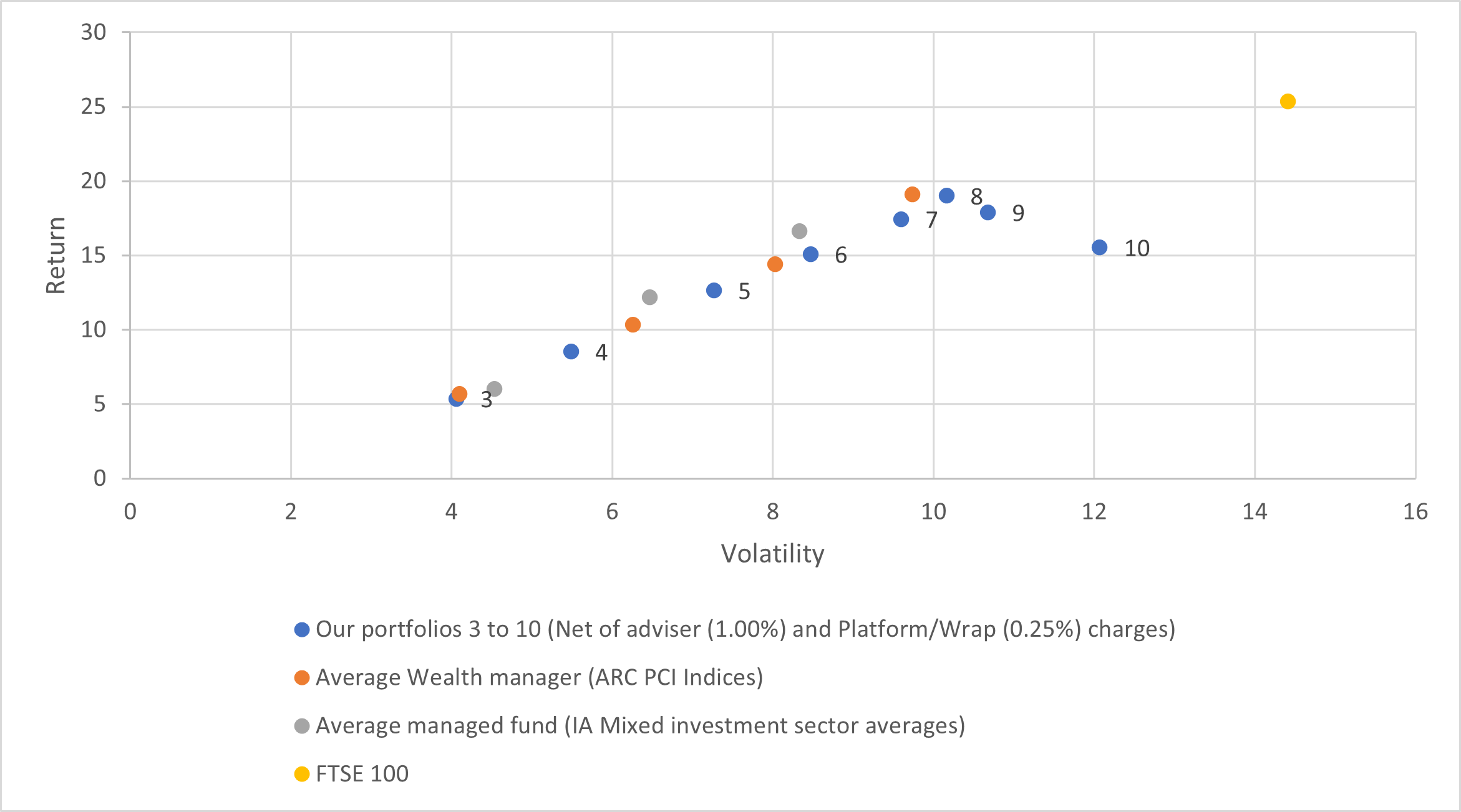

Over the last year this has also broadly been the case on a risk-adjusted basis:

All data taken from Financial Express.

You should be aware we will not always outperform. We stick to a set level of risk and refrain from trying to time the markets. Over the short term, this may lead to underperformance especially when others decide to take more risk which could backfire. Over the long term, our investment process should help our clients get suitable returns.

For more information about our portfolios, you can find the factsheets here and a summary of how we put them together here.

Be aware that past performance is not an indicator of future returns. Markets can go down as well as up.